I became slightly confused, and more than a little overwhelmed. What exactly did this have to do with conservation? I couldn’t quite make the correlation between the hands-on specimen treatments that I had anticipated that I’d be doing, and now discovering that I’d be taking a survey of available space and condition on an entire storage floor of the Department of Paleontology. Lisa and Chris, my supervisors, had been so incredibly nice and so accommodating that I was almost afraid to ask, for fear of coming off as unwilling. But luckily, as it turned out, the answer presented itself to me without my ever even needing to inquire. Conservation of the specimens themselves within a collection is almost a moot point without first employing a bit of collections management. I guess I’d been so used to looking at things on a micro level (having just finished up a term position in archaeological textile conservation) that I’d slowly been losing a sense of the bigger picture. When approaching a new collection, it makes total sense to first survey it and get a sense of what you are working with. Only then can you prepare more specifically and plan around the collection’s needs. Now it has become obvious to me that you first need to gauge how much material you need, how much time it will take, how many conservators will be necessary, how one should distribute a budget, etc. It would be impossible to just start at one end of the room and fix every specimen one by one down the line – funds would be extinguished in a heartbeat without even taking care of those specimens in the worst and most dire condition! Gaining a scope of the work that will be needed is absolutely integral, as well as prioritizing the work and immediacy needed by the specimens that are to be addressed.

I became slightly confused, and more than a little overwhelmed. What exactly did this have to do with conservation? I couldn’t quite make the correlation between the hands-on specimen treatments that I had anticipated that I’d be doing, and now discovering that I’d be taking a survey of available space and condition on an entire storage floor of the Department of Paleontology. Lisa and Chris, my supervisors, had been so incredibly nice and so accommodating that I was almost afraid to ask, for fear of coming off as unwilling. But luckily, as it turned out, the answer presented itself to me without my ever even needing to inquire. Conservation of the specimens themselves within a collection is almost a moot point without first employing a bit of collections management. I guess I’d been so used to looking at things on a micro level (having just finished up a term position in archaeological textile conservation) that I’d slowly been losing a sense of the bigger picture. When approaching a new collection, it makes total sense to first survey it and get a sense of what you are working with. Only then can you prepare more specifically and plan around the collection’s needs. Now it has become obvious to me that you first need to gauge how much material you need, how much time it will take, how many conservators will be necessary, how one should distribute a budget, etc. It would be impossible to just start at one end of the room and fix every specimen one by one down the line – funds would be extinguished in a heartbeat without even taking care of those specimens in the worst and most dire condition! Gaining a scope of the work that will be needed is absolutely integral, as well as prioritizing the work and immediacy needed by the specimens that are to be addressed.Basically, this is where I come in. The aim of my project is to rank and assess the urgency of care of the fossil horse collection of the Paleontology Department (which is totally appropriate since there is a great exhibit on horses going on in the museum right now), as well as to chart the space available for expansion.

Basically, the storage rooms themselves, as well as the storage cabinets, have been updated and rearranged recently to meet more current conservation standards (for example, getting new steel archival cabinets with rubber seals instead of older non-archival wooden ones). The entire project was spearheaded by Chris and Jeanne and has taken years to complete. The scope of the project is ENORMOUS and funding (as is usual with museums) has had to be stretched thin and made to go far. However, despite the tremendous overarching progress that they’ve made, the collections still have a ways to go in order to stabilize all of the individual fossils. They need attention on a more minute level, which is very costly. Essentially, my aim is to get a grasp on how they have been holding up in the meanwhile. However, there is no real established method for doing my kind of work, which is also one of the goals of this project: to develop a process. As you’ve probably assumed, it’s tremendously time consuming and costly for staff to just go through one by one and look at each specimen. In a collection of hundreds of thousands to millions of fossils, it would take ages just to see what you’ve got, not to mention get an accurate estimate of what more you need. Not only is time money, but also it would be at the expense of the fossils, which would be crumbling  away in the meanwhile. So my task is to try and streamline the process with Lisa and Chris, with the objective being to standardize an effective process.

away in the meanwhile. So my task is to try and streamline the process with Lisa and Chris, with the objective being to standardize an effective process.

We’ve already researched many, many articles published by museums worldwide on how to approach a job of such magnitude, and we’ve been working hard to tailor my survey to the specific needs of the Paleontology Department’s collections. So far, we have put together a fantastic and efficient template that makes my work both quicker and easier, without sacrificing the individual needs of the collection (but more about that later on...). So far, with my IPOD to keep me energized, and a ladder to keep me practical (I’m barely 5’1”), I have finished the first portion of my survey, which was to assess all the available space in the collections – and it only took me about a week! It is actually pretty nice to be a test subject in establishing your own process and rhythm to working efficiently. Not to mention, I had completely underestimated how downright AWESOME it is to be able to basically snoop around in the collections (which kinda resemble a scene out of Indiana Jones)! In fact, I was explicitly told to leave no drawer unopened. Think about it – being given the green light to explore the storage rooms of the best museum in the world! It has completely changed my view of museums in general: from sterile cold showrooms, into literal treasure troves of education and caretaking.

away in the meanwhile. So my task is to try and streamline the process with Lisa and Chris, with the objective being to standardize an effective process.

away in the meanwhile. So my task is to try and streamline the process with Lisa and Chris, with the objective being to standardize an effective process.

We’ve already researched many, many articles published by museums worldwide on how to approach a job of such magnitude, and we’ve been working hard to tailor my survey to the specific needs of the Paleontology Department’s collections. So far, we have put together a fantastic and efficient template that makes my work both quicker and easier, without sacrificing the individual needs of the collection (but more about that later on...). So far, with my IPOD to keep me energized, and a ladder to keep me practical (I’m barely 5’1”), I have finished the first portion of my survey, which was to assess all the available space in the collections – and it only took me about a week! It is actually pretty nice to be a test subject in establishing your own process and rhythm to working efficiently. Not to mention, I had completely underestimated how downright AWESOME it is to be able to basically snoop around in the collections (which kinda resemble a scene out of Indiana Jones)! In fact, I was explicitly told to leave no drawer unopened. Think about it – being given the green light to explore the storage rooms of the best museum in the world! It has completely changed my view of museums in general: from sterile cold showrooms, into literal treasure troves of education and caretaking.

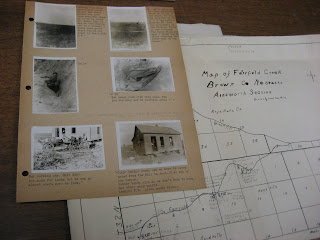

Like I said, I have been working with the fossil horses, and it’s completely fascinating. I can’t say that I’d had any prior experience in horses, but these fossils are amazing – from the imposing skulls to the intricately grooved teeth. Some of the fossils  themselves are practically fossils twice over – they were excavated and brought to the museum over 100 years ago! Even the boxes they arrived in are awesome – sometimes they are in old metal film canisters, sometimes they are crammed into old (now antique) cigarette boxes, and

themselves are practically fossils twice over – they were excavated and brought to the museum over 100 years ago! Even the boxes they arrived in are awesome – sometimes they are in old metal film canisters, sometimes they are crammed into old (now antique) cigarette boxes, and  covered with the most sprawling, beautiful early 20th century calligraphy. Sure, there have been times where my work started to feel a little bit tedious (more so because of the constant climbing up and down that ladder), but it was quickly overruled by the sense of accomplishment I got (and still get!) from knowing how beneficial this work is in preserving what we have, and will be able to study in the future. Whenever a scientist is in the storage room with me, I become aware that there are people who spend their entire lives studying the material that will soon be absent from mine when my project concludes. It reminds me what an absolute privilege it is to be allowed this small window into their lives as well as into the life of a museum community. Everyone around me here has such a tremendous sense of forward thinking from studying the past, and I’m more than happy to keep the condition of at least one collections space running at that same pace.

covered with the most sprawling, beautiful early 20th century calligraphy. Sure, there have been times where my work started to feel a little bit tedious (more so because of the constant climbing up and down that ladder), but it was quickly overruled by the sense of accomplishment I got (and still get!) from knowing how beneficial this work is in preserving what we have, and will be able to study in the future. Whenever a scientist is in the storage room with me, I become aware that there are people who spend their entire lives studying the material that will soon be absent from mine when my project concludes. It reminds me what an absolute privilege it is to be allowed this small window into their lives as well as into the life of a museum community. Everyone around me here has such a tremendous sense of forward thinking from studying the past, and I’m more than happy to keep the condition of at least one collections space running at that same pace.

themselves are practically fossils twice over – they were excavated and brought to the museum over 100 years ago! Even the boxes they arrived in are awesome – sometimes they are in old metal film canisters, sometimes they are crammed into old (now antique) cigarette boxes, and

themselves are practically fossils twice over – they were excavated and brought to the museum over 100 years ago! Even the boxes they arrived in are awesome – sometimes they are in old metal film canisters, sometimes they are crammed into old (now antique) cigarette boxes, and  covered with the most sprawling, beautiful early 20th century calligraphy. Sure, there have been times where my work started to feel a little bit tedious (more so because of the constant climbing up and down that ladder), but it was quickly overruled by the sense of accomplishment I got (and still get!) from knowing how beneficial this work is in preserving what we have, and will be able to study in the future. Whenever a scientist is in the storage room with me, I become aware that there are people who spend their entire lives studying the material that will soon be absent from mine when my project concludes. It reminds me what an absolute privilege it is to be allowed this small window into their lives as well as into the life of a museum community. Everyone around me here has such a tremendous sense of forward thinking from studying the past, and I’m more than happy to keep the condition of at least one collections space running at that same pace.

covered with the most sprawling, beautiful early 20th century calligraphy. Sure, there have been times where my work started to feel a little bit tedious (more so because of the constant climbing up and down that ladder), but it was quickly overruled by the sense of accomplishment I got (and still get!) from knowing how beneficial this work is in preserving what we have, and will be able to study in the future. Whenever a scientist is in the storage room with me, I become aware that there are people who spend their entire lives studying the material that will soon be absent from mine when my project concludes. It reminds me what an absolute privilege it is to be allowed this small window into their lives as well as into the life of a museum community. Everyone around me here has such a tremendous sense of forward thinking from studying the past, and I’m more than happy to keep the condition of at least one collections space running at that same pace.

This is a box full of Dinohippus fossil foot/ankle bones. The Perissodactyl project is working to upgrade storage conditions (the box above is a collection manager's worst nightmare), and part of that is lining drawers, but another important part is keeping track of how many specimens in the horse cabinets are uncatalogued (have not been assigned an AMNH number and therefore have not been officially added to the paleontology catalog).

This is a box full of Dinohippus fossil foot/ankle bones. The Perissodactyl project is working to upgrade storage conditions (the box above is a collection manager's worst nightmare), and part of that is lining drawers, but another important part is keeping track of how many specimens in the horse cabinets are uncatalogued (have not been assigned an AMNH number and therefore have not been officially added to the paleontology catalog).